Co-Authors & Researchers: Areeba Fatima & Umer Zaib Khan

Legal Researchers: Hassan Qaiser Khan & Aiman Butt

Editorial Support: Sarah Fariduddin, Noor Iman Khan

Data Visualization: Danial Sadiq Masood

Digital & Design Support: Murtaza Kapasi & Wajiha Wajih

Co-Authors & Supervisors: Zainab Husain & Sofyan Sultan

Claim

An interim statement by the Commonwealth Observers Group, published on 10 February 2024, characterised the Pakistani general elections held on 8 February 2024 as “generally managed efficiently” in “a largely peaceful environment”. The statement also claims that elections took place “against the background of a substantially reformed and improved legal framework”, before noting “continued efforts at promoting transparency, with the display of the signed Form 45 [polling station results] outside each polling station after counting concluded.”

Fact

Contrary to the interim statement, the 8 February 2024 elections were neither managed efficiently nor held in a largely peaceful environment. Important legal reforms, such as the use of electronic voting machines, and granting the right of franchise to overseas Pakistanis, were either amended, overturned, or made inoperable before the election, adversely affecting transparency and depriving franchise to millions of Pakistanis. Cellular and internet services were suspended on the day of the election, and the election management system was unable to function.

Most significantly, Form 45s were not displayed outside polling stations: they were only uploaded to the Election Commission of Pakistan website three weeks after the election day, violating the legal deadline prescribed by the Election Rules.

Additionally, dozens of candidates were expelled from polling stations, sometimes violently, and denied their legal right to observe the counting of votes. In the end, belatedly released official results contradicted publicly available data from polling stations, and led to the ECP’s results being challenged by nearly 400 candidates, whose petitions have been filed before 23 election tribunals.

Source: The Commonwealth

The Commonwealth Observers Group

The Commonwealth Observers Group (COG) has deployed missions composed of multidisciplinary experts to monitor elections in Commonwealth member states since 1980 . According to their guidelines, COG aims to assess the fairness and credibility of electoral processes and offer recommendations for improvement.

Usually led by a former or current head of state or government, COG’s missions typically include politicians, diplomats, lawyers, human rights activists, journalists, and election administrators, and are designed to operate independently and impartially. Each mission ordinarily publishes its findings and conclusions in an interim statement, followed, shortly thereafter, by a final report. The 13-member COG mission to Pakistan was chaired by former Nigerian president Dr Goodluck Jonathan.

Dr Goodluck Jonathan at a press conference. Source: The Commonwealth

The text of COG’s interim statement on the Pakistan General Elections 2024 repeatedly referred to a forthcoming final report as a more consolidated version of their findings. However, no such final report has been released. The unusual absence of a final report, over seven months after the election, leaves the interim statement as the sole reflection of the group’s assessment.

The Interim Statement

COG released its interim statement on Pakistan’s general elections, on 10 February 2024 at a press conference in Islamabad, with the head of the mission seated alongside the then Caretaker Federal Interior Minister Dr Gohar Ejaz.

Head of Commonwealth Observer Group Goodluck Jonathan addresses a press conference, on 10 February 2024. Source: Tanveer Shahzad/ Dawn News

The statement, which paints a largely positive picture of the elections, includes several claims that Soch Fact Check found to be either false or misleading. The most significant of these claims are as follows:

- “It is noted that the 2024 General Elections took place against the background of a substantially reformed and improved legal framework, initiated prior to the previous general elections in 2018.”

- “We are encouraged by the efforts of the Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP) in seeking to improve election management processes through the introduction of an Election Management System (EMS). We note, however, that the EMS could not operate as intended on Election Day. I will comment on this shortly, in our Election Day observations.”

- “I commend all polling and security officials for ensuring the safety and security of polling stations and enabling the people of Pakistan to exercise their right to vote.” and “While we received reports of some incidents on Election Day, which we will consider further in our final report, voting took place in a largely peaceful environment.”

- “While party candidates’ agents were present in most polling stations observed, there were isolated cases of agents not being accommodated in some polling stations during the voting process and, in addition, they could not properly observe the count.”

- The count at polling stations we observed was generally managed efficiently by polling staff”

- “As during previous general elections, we noted the continued efforts at promoting transparency, with the display of the signed Form 45 outside each polling station after counting concluded. We note that these forms were due to be sent via the mobile phone application, but the shutdown of internet and mobile coverage compelled presiding officers to rely solely on manual transmission of the forms. We received reports that this adversely impacted the processing of results. We will reflect on this further in our final report.”

What do other observers say?

Contrary to COG’s interim statement, Pakistan’s General Election 2024 was, and remains, the subject of much controversy. Numerous human rights organisations, news outlets, foreign governments, and election observers immediately expressed concerns about the pre-poll environment, the electoral process, and the authenticity of the official results announced by the Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP). Since then, criticism of the election has continued to grow.

Significantly, by the time COG published its report at noon on 10 February 2024, first-hand accounts of polling irregularities were already viral on social media; these accounts were reproduced and extensively covered by the local and international press, and corroborated by other election monitors.

Moreover, prominent candidates had already filed petitions in the courts as early as 9 and 10 February, challenging the results and alleging rigging and electoral fraud. Remarkably, COG report failed to mention any of these well-known facts, putting it at odds with the global discourse, and disregarded social media and primary reporting about the elections at that time.

In stark contrast to COG’s statement, the European Union’s (EU) statement, published on 9 February, painted a different picture, saying, “We regret the lack of a level playing field due to the inability of some political actors to contest the elections, restrictions to freedom of assembly, freedom of expression both online and offline, restrictions of access to the internet, as well as allegations of severe interference in the electoral process, including arrests of political activists.” Furthermore, the EU called upon the Pakistani authorities to launch a full investigation of the election irregularities.

The Free and Fair Election Network (FAFEN) report, published on 10 February, echoes the EU statement. FAFEN observers were refused access to polling stations by Reporting Officers (ROs) in 135 constituencies, contravening Section 238 of the Elections Act, 2017, which requires independent observation of all stages of election result preparation— a vital measure for electoral transparency.

Human rights groups criticised the election as well. In a statement posted on 8 February, Amnesty International, categorised the internet shutdown on election day as an “attack on human rights”. Similarly, in an article published on 12 February 2024, Human Rights Watch stated that the “elections were marred by the authorities’ widespread clampdown on freedom of expression and association.”

The Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) also issued a press release on 17 February 2024 demanding an independent audit of the 2024 elections. The press release stated, “Reports from HRCP’s election observers, who carried out spot-checks across 51 constituencies, indicate that the countrywide internet and cellular services shutdown on polling day and arbitrary changes in polling information compromised voters’ access to polling stations.” It further noted, “The ECP must publish all Forms 45, 46, 48 and 49 in accordance with the Elections Act, 2017. On receiving petitions from aggrieved political parties or candidates, the ECP should order ballot recounts in close contests and especially in cases where the number of rejected ballots exceeds the margin of victory.”

A screen showing the results of Pakistan’s parliamentary elections at the Pakistan Election Commission headquarters, in Islamabad, Pakistan, 9 February 2024. Source: Anjum Naveed/AP Photo

Along similar lines, the Pakistan Institute of Legislative Development and Transparency (PILDAT) published their election report in March, noting that the ECP’s failure to publish Forms 45, 46, 47, 48 and 49 on the ECP website within 14 days raises questions regarding the integrity of election results.

Crucially, COG’s statement failed to mention the most significant concern regarding the election: the suspension of the announcement of election results on the night of the election, and the subsequent discrepancy between the results announced by the ECP on 9 February and the results provided to the candidates and broadcast on media on the night of 8 February, immediately after the election.

ECP WEBSITE HAS STOPPED WORKING

GEO NEWS ELECTION WEBSITE HAS STOPPED WORKING

HUM NEWS ELECTION WEBSITE HAS STOPPED WORKING

next level rigging taking place behind the scenes

— Areeba (@arieba_chaudryy) February 8, 2024

[X post embedded here. Use vpn to view in Pakistan]

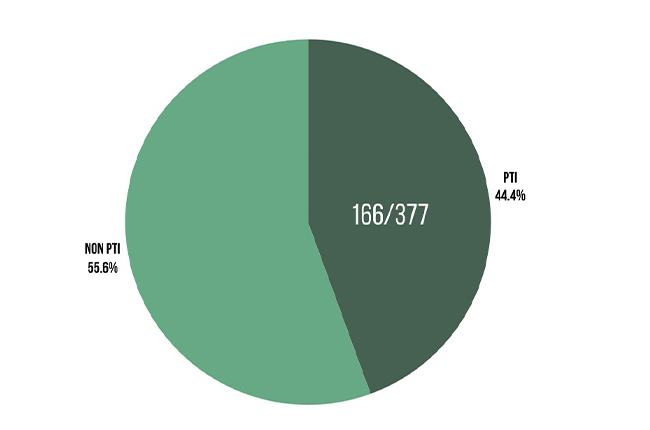

Soon after polling had concluded, at least three petitions challenging the election results were filed in the High Courts of Lahore and Sindh. This information was confirmed by Soch Fact Check through conversations with lawyers Ali Tahir, Salman Akram Raja, and Taimur Malik, who provided the relevant documents to corroborate their claims. By the end of February, election results for the provincial and national assemblies were challenged in nearly 80 constituencies. However, COG did not include or update its interim statement to acknowledge these developments. At the time of the publication of this article, almost all of those legal challenges remain sub judice. According to a FAFEN report, as of 20 June, “at least 377 election petitions challenging the outcomes of as many National and Provincial Assembly constituencies have been submitted for consideration of 23 election tribunals appointed by the ECP”. At least 166 petitions out of the 377 were filed by PTI-backed independent candidates, as confirmed to us by the PTI’s Election Management Cell. Furthermore, FAFEN’s most recent update noted the delay in resolving these petitions, adding that only seven percent of the total petitions have been resolved by the ECP as of 17 August 2024, as the legal deadline of 180 days, set by the Elections Act, 2017, drew closer.

Number of election petitions filed in tribunals challenging election results since 8 February 2024

More recently, on 25 June 2024, the US House of Representatives passed a resolution urging a “full and independent investigation of claims of interference or irregularities in Pakistan’s February 2024 election.” The resolution, which was passed by 368-7, specifically states that “Pakistan’s 2024 general election was marked by allegations by credible international and local observers of interference in the electoral process, including electoral violence, intimidation, arrest of political actors, restrictions to freedom of assembly, restrictions on freedom of expression, and restrictions on access to the internet and telecommunications.”

Pre-Poll Environment

A series of election delays

The Pakistani political climate, during the years prior to the election, was dominated by a constitutional crisis set in motion by the removal of Imran Khan’s PTI government via a vote of no confidence on 10 April 2022. This crisis was marked and intensified by a series of delays in conducting elections, both in the provinces and in the Federation — a highly relevant series of events that COG report fails to mention.

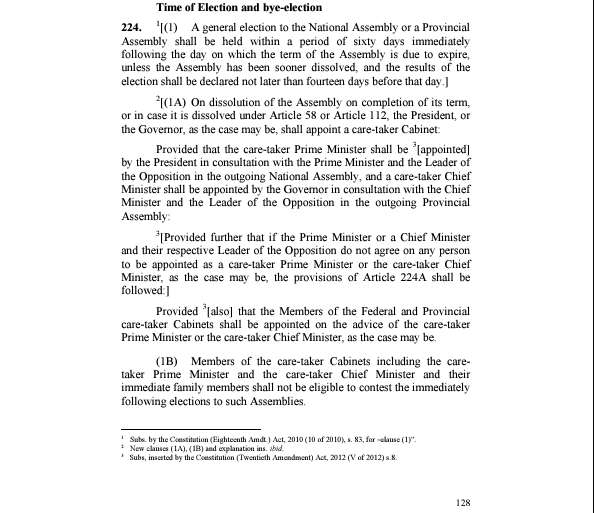

Caption: PTI Chairman Imran Khan addresses a rally in Jhelum in May 2022. — Imran Khan Twitter

After the ouster of their government at the Centre, in order to force early elections, the PTI dissolved the Punjab Assembly on 14 January 2023, followed by the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK) Assembly four days later. According to Article 224 of the Constitution of Pakistan, elections must be held within 60 days of an assembly completing its term, or within 90 days if an assembly is dissolved prematurely. This interpretation was upheld by the Supreme Court in their 4 April 2023 judgement, which also ordered different ministries to perform specific functions to aid the ECP in conducting the elections. However, despite the judgement, the Finance Ministry refused to provide funds and the Defense Ministry claimed they could not provide security. The ECP consequently claimed that due to security threats and financial constraints, they couldn’t hold elections in either province until October 2023. As a result, elections in both provinces failed to take place within the constitutionally mandated period, and unelected caretaker governments remained in office in both Punjab and KPK for over a year – an event unprecedented in the history of the country.

Article 224: Time of Election and bye-election. Source: Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan

As the National Assembly’s term was due to end on 12 August 2023, on 5 August 2023, Prime Minister Shahbaz Sharif convened a meeting of the Council of Common Interests (CCI) and approved the latest census, which had itself been delayed several times. As the Constitution mandates that general elections must follow the delimitation of constituencies based on the latest census, the last-minute approval of the census provided the ECP with administrative grounds to delay countrywide elections yet again. The Prime Minister then proceeded to dissolve the National Assembly on 9 August 2023, three days before the end of its term, as the Constitution specifies that if assemblies complete their term, elections must occur within 60 days, but if dissolved early, they must be held within 90 days. This early dissolution provided additional grounds for further delays.

After several months of uncertainty, the ECP finally submitted a notification in the Supreme Court, fixing the date of General Elections as 8 February 2024, nearly six months after the dissolution of the assemblies.

Lawmakers of the National Assembly arriving for a group photo with Pakistan’s Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif in Islamabad on Wednesday. Source: Anjum Naveed/Associated Press

Intimidation and Violence against Candidates

At the same time, while elections were being delayed, thousands of ordinary members of the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) – as well as other protesters and those expressing dissent on social media – were either arrested or arbitrarily detained by intelligence and law enforcement agencies.

Following the riots on 9 May 2023, after Imran Khan’s illegal arrest, many PTI leaders, workers, and supporters faced charges in anti-terrorism and military courts. The continuing use of military courts to try civilians has been condemned by several human rights organisations but found no mention in COG report.

Khan’s supporters protesting against his arrest in Lahore on 9 May 2023. Source: K M Chaudary/AP Photo

Senior PTI leadership and other PTI politicians also faced arrests and abductions, both before and after the events of 9 May 2024. Notable figures who were arrested, detained, or abducted, include former foreign minister Shah Mahmood Qureshi, former Human Rights Minister Shireen Mazari, Hassan Khan Niazi, Dr Yasmin Rashid, former Finance Minister Asad Umar, Ali Muhammad Khan, Senator Ejaz Chaudhry, Firdous Shamim Naqvi, Shehryar Khan Afridi, Shandana Gulzar, Omar Sarfaraz Cheema, Haleem Adil Sheikh, Falak Naz, Aliya Hamza Malik, Farrukh Habib, Murad Saeed and Usman Dar. Many of those detained were electoral candidates who remained in jail until after the elections, or are still in jail today. In many cases their family members were detained as well, often without charge.

Of those who were released, after being abducted or arbitrarily arrested, several alleged that they had been subject to torture at the hands of the authorities, while others bore visible signs of torture and maltreatment. This list includes various PTI leaders, including Shahbaz Gill and Azam Swati.

PAKISTAN: Amnesty International is concerned about the allegations of torture being made by the lawyers of @SHABAZGIL, and calls for an immediate, effective and impartial inquiry investigating these claims.

— Amnesty International South Asia, Regional Office (@amnestysasia) August 19, 2022

[X post embedded here. Use vpn to view in Pakistan]

Prominent journalists were also abducted, such as Imran Riaz Khan who remained missing for nearly four months. Amnesty International termed Imran Riaz Khan’s arrest an “enforced disappearance”, a position echoed by CIVICUS Monitor and the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ). In June 2023, prominent human rights defender Jibran Nasir was abducted by intelligence agencies as well.

Lawyer Jibran Nasir speaks to the media in Karachi after his return on 2 June 2023. Screengrab

Journalists based outside of Pakistan were also targeted by the authorities when the Islamabad police opened an investigation against multiple journalists for allegedly “inciting people to attack military installations, spread terrorism, and create chaos” on 9 May. “It is unconscionable that foreign-based Pakistani journalists Wajahat Saeed Khan, Shaheen Sehbai, Sabir Shakir, and Moeed Pirzada face potential death sentences under terrorism investigations in retaliation for their critical reporting and commentary,” said Beh Lih Yi, CPJ’s Asia program coordinator. In June, an anti-terrorism court in Islamabad instructed the Chairman of Nadra, and the Director General of FIA to block the identity cards, NICOPs, and passports of these journalists. Earlier, prominent journalist Arshad Sharif fled Pakistan due to death threats, before being murdered in Kenya under suspicious circumstances.

People attend the funeral prayer of slain senior Pakistani journalist Arshad Sharif, in Islamabad, Pakistan. Source: Anjum Naveed/AP Photo

In many cases authorities employed tactics of arrest and rearrest in order to extend detentions. Imaan Mazari, Ali Wazir, Khadija Shah, and Aliya Hamza, amongst others, faced a series of arrests and rearrests on poorly substantiated charges of terrorism and damaging public property.

Khadija Shah being taken by police from the courtroom on 24 May 2023 in this still taken from a video. — Source: Geo.tv

This pattern of arrest and rearrest was also employed against Imran Khan himself, who was rearrested on 5 August, 2023, and has remained in jail ever since, on one charge or another. On 21 October, the Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP) barred Khan from holding public office for five years in the Toshakhana reference case.

The UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention has since declared Imran Khan’s detention as politically motivated and arbitrary, citing a lack of legal justification, an intent to prevent him from exercising fundamental rights, and a denial of a fair trial. Notably, three of his convictions took place in quick succession, via midnight hearings conducted in jail, in the weeks immediately prior to the election, when he was further banned from holding public office for 10 years. In particular, Imran and Bushra Khan’s conviction for conducting an “illegal marriage” drew widespread condemnation from civil society and human rights groups.

Imran Khan leaves after appearing in a court, in Lahore, Pakistan, on 7 June 2023. Source: K.M. Chaudary/AP

As such, contrary to COG’s characterization, the weeks and months prior to the election were marked by large-scale violations of human rights carried out by state authorities. Violations of human rights – including universally recognized fundamental rights guaranteed by the Pakistani Constitution such as the freedom of association (Article 17), security of person (Article 9), safeguards as to arbitrary arrest and detention (Article 10), the rights to fair trial (Article 10A), and freedom of speech (Article 19) – were systematic, targeted, and commonplace.

The Bat Decision

On 22 December 2023, amid the severe repression against the PTI and its candidates, described above, the Election Commission of Pakistan declared the PTI ineligible to obtain the election symbol for which it had applied, i.e. the bat, due to the supposed absence of intra-party elections.

Order regarding PTI intra party election and ineligibility to obtain symbol bat https://t.co/ligBkvyVfF

— Election Commission of Pakistan (OFFICIAL)🇵🇰 (@ECP_Pakistan) December 22, 2023

[X post embedded here. Use vpn to view in Pakistan]

In response, the PTI filed a petition before the Peshawar High Court (PHC) to challenge this order of the ECP, which led to the PHC upholding the PTI’s constitutional right to contest the election under a common symbol and setting aside the ECP’s decision.

Immediately thereafter, the ECP appealed this decision before the Supreme Court. The appeal was heard over the next three days, in perhaps the fastest appeal proceedings in the Court’s history, before the expiration of the ECP’s deadline for the allotment of electoral symbols. On 13 January 2024, the Supreme Court came to the historically unprecedented decision that the PTI was ineligible for the allocation of an election symbol.

This judgement was widely criticised as being a politically motivated and undemocratic intervention to deny the PTI a fair chance in the election. Other parties judged to have not held intra-party elections were not subjected to the same sanctions.

View of the Supreme Court of Pakistan in Islamabad, Pakistan 4 April 2022. Source: Reuters

Internet Disruptions

Further, as election day drew near, Pakistanis faced a series of social media disruptions and internet outages. These disruptions often coincided with the dates on which PTI was scheduled to hold ‘virtual rallies’ and fundraisers.

The HRCP’s report on the State of Human Rights in 2023 noted the several internet and social media outages reported during the year, adding that “Bytes for All, a Pakistani internet rights group, counted at least 15 internet shutdowns in 2023.” In particular, the report addressed the impact of the shutdowns following the PTI-led protests on 9 May. “Citizens especially suffered prolonged mobile network and social media outages following the 9 May riots, with services only gradually restored several days after”, the HRCP noted.

Closer to the election, nationwide internet outages and disruptions on 17 December 2023, 7 January 2024, and 20 January 2024, were analysed and documented by global internet monitors such as Netblocks and Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI). Based on the findings published by OONI on 7 February, “ISPs in the country blocked access to the websites of the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) political party (one of Pakistan’s largest political parties), as well as to an investigative news platform (Fact Focus),” in the days leading up to the General Elections 2024.

[X post embedded here. Use vpn to view in Pakistan]

Notably, each time a disruption occurred, the government officials denied that any deliberate intervention had taken place, and instead claimed that the disruptions were due to “technical glitches”. However, according to internet watchdog Netblocks, the incidents of internet disruption were “consistent with previous social media filtering events which have all been imposed during opposition party rallies or speeches by opposition leader Imran Khan.”

Election-Day and Day-After Irregularities

The following timeline delineates significant and well-documented irregularities, relevant to the assessment of the Pakistan Elections 2024, that took place on and around election day. The below irregularities, left out by COG’s interim statement, occurred between 7 February 2024 and 12:00 pm on 10 February 2024 when the interim statement was published.

On the night of

7 February 2024

Prime Minister Anwar ul Haq Kakar assured the public that his government had “no intention” of shutting down internet services, in response to concerns over potential disruptions due to repeated social media outages in the weeks and months before the election. This was echoed in a previous statement made by the Chief Election Commissioner Sikander Sultan Raja, who said, amid the internet shutdown, that the EMS is not dependent on the Internet and its work will not be affected due to it.

Around 7:30 am on

8 February 2024

Despite these assurances the government implemented a nationwide shutdown of cellular networks. The decision caused several technical difficulties, such as the suspension of NADRA’s Voter Registration (8300) service which was designed to enable voters to find their polling station. The decision was criticised by human rights organisations, and international observers, including Human Rights Watchand Amnesty International.These criticisms stood in stark contrast to the statementmade by COG mission leader Dr Goodluck Jonathan, on the day prior, in which he claimed, “Before the invention of the internet, we were holding polls and voting is more important than the internet”. In the same statement, he implied that the suspension would not impact voters, adding that, “Voting process does not require internet, however, the suspension of internet services would only create trouble while posting the poll results,” thereby providing authorities with a carte blanche for internet services to be suspended the very next day.

7:52 am on

8 February 2024

Eight minutes before polling was scheduled to begin, the Ministry of Interior published a statement in Urdu, saying that in response to “recent incidents of terrorism” in the country, cellular networks had been cut off “to maintain the law and order situation and deal with possible threats.”

8:00 am – 6:00 pm on

8 February 2024

Polling began. The military and local police reported over 51 attacks on polling stations between 8:00 am and 6:00 pm that killed 12 and injured 39 in various parts of the country, according to the Associated Press. Furthermore, the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) said that the polling process was disrupted on the day of elections as armed Baloch separatist groups targeted multiple polling stations with grenades and explosives. The then Caretaker Interior Minister Dr Gohar Ejaz, claimed 16 people were killed in 56 incidents of violence during general elections. Interestingly, these incidents of violence were not mentioned in COG’s interim statement at all.

6:00 pm on

8 February 2024

Soon after polling closed at 5 pm, the media began announcing results, which were based on Form 45s that were acquired by election reporters from contesting candidates, and consolidated by media channels.

6:00 pm on

8 February 2024

6:30pm to 12:00am on

8/9 February 2024

Numerous sources, including national and international media, reported that unofficial results showed PTI-affiliated candidates in the lead.

After 8 pm on

8 February 2024

Dozens of candidates documented their illegal expulsions from RO offices on social media. Expulsions were reported by a candidate from NA 31 Peshawar (8:31 pm), a candidate from NA 128 Lahore (10:07pm), various (1:00 am) candidates (1:35 am) from more than 20 constituencies in (8:39 pm) Karachi (2:02 am), and in NA 48 Islamabad (10:08 pm). Mainstream publications also documented that RO offices and polling stations were cordoned off, while journalists and party representatives were prevented from entering. These facts are directly at odds with COG’s claim that the counting of votes was managed efficiently.

At 10:54 pm on

8 February 2024

US congresswoman Rashida Tlaib weighed in on Pakistan’s elections on X, saying the country’s democracy is “at serious risk”. Tlaib added that Pakistani people “should be able to elect their leaders without interference and tampering with the process”. Soon after, a large number of results announced in the media showed that PTI was in the lead, and that the pace of election results had slowed down. Subsequently, Congressman Brad Sherman posted on X, urging that “there should be no unwarranted delay in announcing results.”

Around 3 am on

9 February 2024

Various news organisations reported results, based on available Form 45s, showing PTI candidates in the lead in at least 150 constituencies. The number of seats won by each party unofficially, in the National Assembly, was reported by digital media channels., However, the live broadcast election coverage from this time has now conspicuously been removed by major news channels, including Geo News, Hum News, ARY News, and Dawn. The live video-stream of results from the night of 9 February 2024, that was previously available on their YouTube channels, has been deleted.

3:00 am on

9 February 2024

There was no official announcement of results for any of the constituencies, whether provincial or national assembly, until 10 hours after polling time had ended. In contrast, Al Jazeera reported that in the previous election, results had started to emerge within two to three hours after polls closed. By 3 am, the ECP announced the first official result, declaring two independent candidates successful for KP assembly seats. Special Secretary Zafar Iqbal appeared on the state-run PTV, and announced the first official result for the KP provincial assembly. During his address, he blamed the unavailability of cellular internet for the delay in compilation of the results. Under Rule 84 of the Election Rules, results should have been communicated by the ROs to the ECP by 2 am in the morning and made public shortly thereafter. If, under the Rules, the returning officers had incomplete results by this time, they were legally bound to tell the ECP why and indicate which vote counts were still awaited. In fact, more than 13 hours after the polls formally closed, the election commission had announced just eight results out of 266 in the National Assembly.

On the morning of

9 February 2024

Salman Akram Raja, a candidate from NA 128 Lahore, challenged his expulsion from the RO’s office in his constituency in the Lahore High Court (LHC). His arguments were heard by Justice Baqir Najafi, who then restricted the ECP from announcing a winner in NA 128. It was also noted in court that the results of only 13 polling stations in the constituency had been declared in the presence of the petitioner’s representatives.

12:00 pm on

9 February 2024

Voice of America published a report saying, “Based on local constituency counts, unofficial overnight tallies from Pakistani media outlets showed PTI-backed candidates leading races nationwide. In some cases, they were ahead by 30,000 to 50,000 votes. However, according to early official results released on Friday, they were either lagging behind or lost the race by a small margin.”

7:02 pm on

9 February 2024

PTI-backed independent candidate, from NA 256 Karachi, Alamgir Khan presented alarming claims of contradictions between the Form 45s issued to him and his polling agents on 8 February and the results of Form 47 issued the next day by the ECP.

2:24 am on

10 February 2024

The Guardian reported that the PTI-backed candidates had claimed “a stunning victory after Thursday’s polls, defying all expectations that Sharif, a three-time former prime minister, and his Pakistan Muslim League (PML-N) would win an easy majority.” Within the same hour, The Washington Post also reported that candidates affiliated with the ex-premier Khan’s party “appeared to have performed well above expectations, according to provisional official results for more than 90 percent of the races.” The New York Times further corroborated news of the PTI’s lead, adding that by the early hours of 10 February, “Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf, or P.T.I., was leading in the polls with at least 90 confirmed seats in the National Assembly, the lower house of Parliament.”

6:51 am on

10 February 2024

Reuters reported that US, UK and European officials released statements calling for a probe into claims of interference and fraud during Pakistan’s elections. The UK foreign secretary, David Cameron, voiced concern over “significant delays to the reporting of results and claims of irregularities in the counting process”.

It is important to note that COG’s interim statement did not mention any of the events or reports listed in this timeline.

Fact-Checking Individual Claims

So far this fact-check has largely focused on facts relevant to the assessment of the fairness and transparency of the Pakistan general elections 2024 that COG failed to include in their interim statement. The remainder of this fact-check will focus upon specific claims contained in COG’s interim statement that are either false or misleading as per IFCN guidelines.

COG report is divided into a total of 17 subsections under four subheadings; Soch Fact Check identified a significant number of false or misleading claims within six of the 17 sub-sections of the report. Relatively less important misleading claims, such as those regarding adverse weather conditions, have been dealt with separately or subsumed within other sections of the document.

| No. | Claim | Rating |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | “It is noted that the 2024 General Elections took place against the background of a substantially reformed and improved legal framework, initiated prior to the previous general elections in 2018.” | False |

| 2 | “We are encouraged by the efforts of the ECP in seeking to improve election management processes through the introduction of an Election Management System (EMS). We note, however, that the EMS could not operate as intended on Election Day. I will comment on this shortly, in our Election Day observations.” | Misleading |

| 3 | “I commend all polling and security officials for ensuring the safety and security of polling stations and enabling the people of Pakistan to exercise their right to vote.”

And “While we received reports of some incidents on Election Day, which we will consider further in our final report, voting took place in a largely peaceful environment.” |

Misleading |

| 4 | “While party candidates’ agents were present in most polling stations observed, there were isolated cases of agents not being accommodated in some polling stations during the voting process and, in addition, they could not properly observe the count.” | False |

| 5 | “The count at polling stations we observed was generally managed efficiently by polling staff”. | False |

| 6 | “As during previous general elections, we noted the continued efforts at promoting transparency, with the display of the signed Form 45 outside each polling station after counting concluded. We note that these forms were due to be sent via the mobile phone application, but the shutdown of internet and mobile coverage compelled presiding officers to rely solely on manual transmission of the forms. We received reports that this adversely impacted the processing of results. We will reflect on this further in our final report.” | False |

-

Legal Environment and Election Administration

Claim: “It is noted that the 2024 General Elections took place against the background of a substantially reformed and improved legal framework, initiated prior to the previous general elections in 2018.”

Rating: False.

Fact: There were no significant improvements to the Election Act, which is the primary legislative framework for general elections in Pakistan and which was in place before the 2018 elections. Previous legislative improvements, such as the introduction of electronic voting machines, and provisions enabling overseas Pakistanis to participate in the electoral process, were repealed or rolled back by the PDM government in the two years prior to the election.

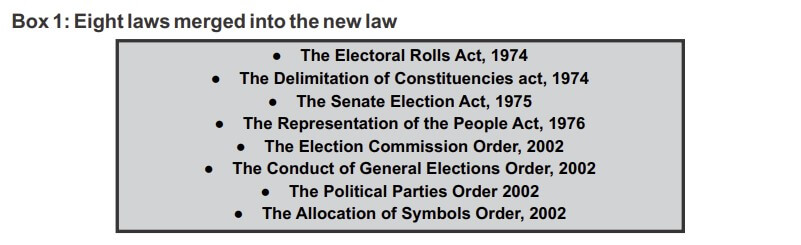

The Elections (Amendment) Act, 2017 was first introduced as the Elections Bill, 2017, under Shahid Khaqan Abbasi’s premiership, after Nawaz Sharif was disqualified. The Act integrated and simplified eight different election-related laws including the Representation of the People Act, 1976, and the Electoral Rolls Act, 1974, into one unified legal framework. It’s relevant to note that the Act was already in place prior to the 2018 General Elections and that no structural changes in the legal framework around elections took place post-2018.

Source: “Background Paper, The Elections Act, 2017: An Overview” by PILDAT

The Act empowered the Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP) with greater autonomy, including rule-making authority, to ensure free and fair elections. It also allowed the ECP to undertake pilot projects for the use of electronic voting machines (EVMs) and biometric voter identification systems in the by-elections, as well as voting by overseas Pakistani citizens.

Key provisions of this law also required political parties to disclose their funding sources, and submit audited accounts. It also mandated measures to facilitate voter registration.

Source: Rebecca Conway/Getty Images

During Imran Khan’s tenure, several clauses of the Election Act, 2017 were amended, granting overseas Pakistani nationals the right to vote, and mandating the use of electronic voting machines (EVMs) for the next elections. This was done through an amendment passed by the parliament in November 2021, enabling the use of EVMs and allowing overseas voting for the next general election, potentially adding nine million more voters to the electoral process.

Prime Minister Imran Khan in parliament on 17 November 2021. Source: Gulf Today

However, after the fall of the PTI government, many of the improvements in the Election Act were undone by the Pakistan Democratic Movement (PDM) government when they assumed power in April 2022. In May 2022, the National Assembly approved a bill, revoking the voting rights of overseas Pakistanis and halting the use of EVMs in general elections. This meant that the extension in enfranchisement, and increase in transparency of the voting process that were promised by the November 2021 amendment in the Election Act, were sacrificed by the PDM regime. An additional amendment in 2023 expanded the powers of unelected interim governments, allowing them to make decisions and continue government projects. Prior to this amendment, interim governments lacked the constitutional authority to make long term decisions which were considered to be the purview of elected governments. This amendment allowed the caretaker government to conduct and conclude negotiations with the IMF and to extend their stay beyond their constitutional mandate. This amendment also transferred the authority to announce election dates from the president to the ECP under Section 57. This empowered the ECP to potentially delay elections.

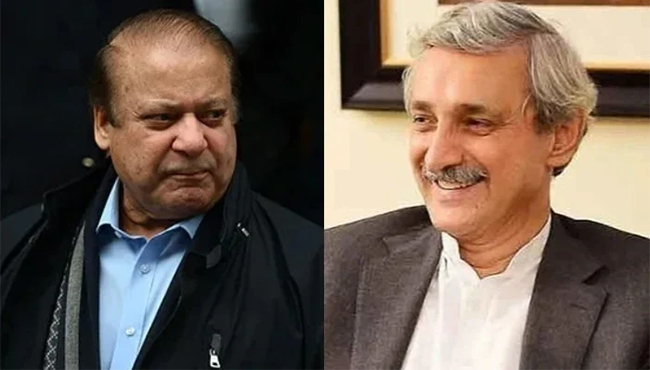

The amendment also reduced the disqualification period for members of parliament to five years, for violations of Articles 62 and 63 of the Constitution. Notably, this provision applied retroactively, potentially benefiting previously disqualified candidates, such as Nawaz Sharif and Jehangir Tareen.

In short, while there was greater consolidation of electoral laws in Pakistan, this happened prior to the 2018 elections, not after. Certain progressive amendments, that expanded the voter franchise and increased transparency, were repealed in 2022 and 2023. New amendments were also made to enhance the ECP’s power to delay elections, expand the powers of caretaker governments, and reduce disqualification periods retroactively. On the whole, these changes do not reflect a “reformed and improved legal framework”.

-

Election Management System (EMS)

Claim: “We are encouraged by the efforts of the ECP in seeking to improve election management processes through the introduction of an Election Management System (EMS). We note, however, that the EMS could not operate as intended on Election Day. I will comment on this shortly, in our Election Day observations.”

Rating: Misleading.

Fact: The EMS was unavailable due to a decision by the interim government to shut down mobile internet on the day of the election. COG’s report did not acknowledge that the EMS fundamentally required mobile internet to function and that the decision to shut down mobile internet, in addition to causing other harms, made it impossible for the EMS to function.

The claim that the Election Management System (EMS) did not function as intended on Election Day fails to consider the primary reason for the EMS’s non-functionality: the government’s deliberate and intentional shutdown of mobile internet.

The ECP’s Results Transmission System (RTS), as prescribed by the Election Act, required Presiding Officers to transmit snapshots of Form 45 using a mobile application. This process necessitated mobile internet to function without delays or disruptions. However, at around 7:30 am on election day, the government implemented a nationwide shutdown of cellular networks despite prior assurances that the internet would not be disrupted.

ملک میں دہشت گردی کے حالیہ واقعات کے نتیجے میں قیمتی جانوں کا ضیاع ہوا ہے، امن وامان کی صورتحال کو قائم رکھنے اور ممکنہ خطرات سے نمٹنے کے لیے حفاظتی اقدامات ناگزیر ہیں، اس لیے ملک بھر میں موبائل سروس کو عارضی طور پر معطل کرنے کا فیصلہ کیا گیا ہے۔ ترجمان وزارت داخلہ

— Ministry of Interior GoP (@MOIofficialGoP) February 8, 2024

[X post embedded here. Use vpn to view in Pakistan]

In fact, on 24 January 2024, the Sindh High Court instructed the federal government as well as the Pakistan Telecommunications Authority (PTA) “to ensure uninterrupted internet access till February 8, when general elections are scheduled to take place in the country”. Consequently, after polling ended, Presiding Officers could not upload results on the EMS and manual processes had to be used instead.

At 3:00 am on 9 February 2024, the ECP’s Special Secretary Zafar Iqbal appeared on the state-run PTV to announce the official result of the KP provincial assembly. During his address, he blamed the unavailability of cellular internet for the delay in the compilation of results and for the EMS not being able to function.

This statement directly contradicted a previous statement made by the Chief Election Commissioner Sikander Sultan Raja, who said, amid the internet shutdown, that the EMS is not dependent on the Internet and its work will not be affected due to it. Further adding to the confusion was the statement made by the Commonwealth Observers Group (COG) mission head Dr Goodluck Jonathan, in which he said, “Voting process does not require internet, however, the suspension of internet services would only create trouble while posting the poll results.”

COG delegation headed by Dr Goodluck Ebele Jonathan inspects polling process during Pakistan general elections on 8 February 2024. Source: X/@commonwealthsec

In their Assessment of the Quality of General Election 2024, released in March 2024, PILDAT noted that since the possibility of an internet shutdown was discussed prior to the election, “the logistics of presiding officers manually transmitting results to returning officers could have been planned ahead.”

Then caretaker interior minister Gohar Ejaz had indeed hinted at the possibility of an internet shutdown on polling day, only two days before the election, and added that, “Before taking any such decision for a specific area, the government would look into the nature of the threat as it is necessary to block the online communication of terrorists”. PILDAT’s Assessment further raised questions about the EMS’ functionality on 8 February, considering that a successful mock test of the system had been announced by the election body, and cited that “the ECP assured the public that the EMS would work seamlessly online and offline, and the chain of transmission of results would not experience any delays”.

Caretaker Interior Minister Gohar Ejaz (R) and caretaker Information Minister Murtaza Solangi address a press conference on election safety in Islamabad on 6 February 2024. Source: AFP

In fact, many observers believed that mobile internet was intentionally turned off to prevent the management system from working. A day before the election, The Intercept published an investigation regarding the steps taken by the military and the caretaker government to subvert the elections. The investigation highlights eight ways through which the election was rigged, one of which was the alleged hacking of the election management system (EMS).

Furthermore, a report published by Dawn.com, on 5 February 2024, highlighted that two election officials had pointed out faults in the Election Management System (EMS) days before 8 February 2024. According to this report, “Abdul Qadir Mashori, the Qambar assistant commissioner (AC), and RO for National Assembly seat NA-197 (Qambar-Shahdadkot-II), and Usman Khaskheli, the Bakrani AC and RO for PS-12 (Larkana-III) seat of Sindh Assembly, have written letters to their superiors, conveying almost identical issues regarding the EMS.”

Just days ahead of elections, election officials claim that NADRA’s Election Management System (EMS) is faulty and unreliable and constantly loses data. pic.twitter.com/l8c2viDSik

— Waqas (@worqas) February 4, 2024

[X post embedded here. Use vpn to view in Pakistan]

In short, while potential technical challenges with the EMS were anticipated, and the EMS was believed by some observers to have been externally compromised, in the end the internet shutdown by the interim government was the primary reason behind the system’s failure, and not internal flaws in the system.

-

Polling environment

Claim: “I commend all polling and security officials for ensuring the safety and security of polling stations and enabling the people of Pakistan to exercise their right to vote.”

And

“While we received reports of some incidents on Election Day, which we will consider further in our final report, voting took place in a largely peaceful environment.”

Rating: Misleading.

Fact: In addition to the many documented human rights violations that took place in the weeks and months leading up to the general elections, COG’s statement also failed to take into account a number of violent incidents that occurred on polling day itself. Given the numerous reports of attacks at polling stations, as well as on candidates, during the general election, it is misleading to state that polling took place in a largely peaceful environment.

Notable incidents of violence included at least three militant attacks, violence between political parties, attacks on polling stations, and the widespread use of state machinery against electoral candidates and party supporters.

People run out of a polling station after a hand grenade attack in the vicinity of Sariab area, Quetta, on election day. Source: AFP

The military and local police reported over 51 attacks on polling stations between 8:00 am and 6:00 pm on election day, resulting in 12 deaths and 39 injuries across various parts of the country, as reported by the Associated Press. Additionally, according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED), armed Baloch separatist groups targeted multiple polling stations with grenades and explosives, disrupting the polling process.

A non-exhaustive list of incidents reported on mainstream and social media is as under:

- Former Member of the National Assembly, Mohsin Dawar tweeted at 10 am on voting day, announcing that the Taliban have attacked three of their polling agents in Tappi, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

Three of our female polling agents in Tappi has been attacked by Taliban. They have escaped the blast very narrowly. I had written to the DRO to change the polling stations in Tappi but my letter was ignored. The ECP has to take notice of the security situation in Tappi urgently.

— Mohsin Dawar (@mjdawar) February 8, 2024

[X post embedded here. Use vpn to view in Pakistan]

- Another report by The Express Tribune, from election day, noted that a political worker sustained a gunshot injury during a brawl in Kotri, Jamshoro district. Gunshots were also reported in Tando Wali Muhammad, where armed men allegedly broke down a ballot box, scattering ballot papers in NA 220.

NA-220 candidate Faisal Mughal caught army jawans doing thappay per thappa at RO office.

These are the sipahis that plastic insafis always defend. These sipahis aren’t “just doing their duty”, they are doing HIGH TREASON & under article 6 they need to be hanged. pic.twitter.com/JobyBD5UST

— F. (@FatiSpeaks_) February 10, 2024

[X post embedded here. Use vpn to view in Pakistan]

- According to this report by Dawn.com, five people were injured during a clash between the PPP and PML-N’s workers at a polling station of Chak 171-P in Sadiqabad tehsil, Rahim Yar Khan.

- A video showing harassment of polling staff, damaged ballot boxes, and active manipulation of the voting public was published on X, at around 5 pm, on election day. It also included members of the polling staff and the public claiming that they were beaten up by unknown assailants in the constituency NA-87.

Na 87 pic.twitter.com/3FtWWsJmux

— TAimoor ArshAd (@taimoorarshad93) February 8, 2024

[X post embedded here. Use vpn to view in Pakistan]

- In addition, according to news reports, multiple people were injured in Karachi in poll-related violence on 8 February. Clashes took place between rival parties in which “four persons including three with bullet injuries” were reportedly brought to hospitals, according to a statement by a police surgeon, while incidents of violence in certain areas of the city were also reported after polling had ended, as reported by Dawn.

Furthermore, immediately after the elections, a number of protests against alleged electoral manipulation were put down with force. Such incidents included the following:

- At noon on 9 February 2024, civilians protesting the cordoning off of RO offices were attacked with shelling in NA 72 Sialkot. According to the videos on social media, protesters were demanding official election results 20 hours after voting had ended.

shelling has started on the citizens gathered outside the RO office in Sialkot (NA-72).

people gathered here because ECP failed to provide them with Form-47 (final result) even after 20 hours. pic.twitter.com/ULwblFuIdC

— dexie (@dexiereborn) February 9, 2024

[X post embedded here. Use vpn to view in Pakistan]

- On 11 February 2024, when Mohsin Dawar protested allegations of rigging outside the ECP office and demanded to be let in, as per his constitutional right to oversee the counting process as a contesting candidate, the police opened fire at him and his supporters in Miranshah Cantonment. As a result, two workers of the National Democratic Movement (NDM) were killed while 15 others were injured.

Mohsin Dawar being shifted to hospital after he was injured in police firing on a protest outside the RO’s office in Miramshah Cantt. Source: Dawn

- According to Al Jazeera, on 12 February, “AFP staff saw police fire tear gas at a crowd of PTI supporters picketing an election office.” The article also noted that, “A gathering of about 200 PTI supporters in Lahore was dispersed quickly after police moved in with riot shields and batons.”

![PTI supporters protest in Peshawar [Abdul Majeed/AFP]](https://www.sochfactcheck.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/cover-image-big.jpg)

PTI supporters protest in Peshawar on 10 February 2024 [Abdul Majeed/AFP]

![Supporters of Khan's Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) party block the Peshawar-to-Islamabad highway as they protest thePakistan's national election results, in Peshawar on February 12, 2024 [Abdul Majeed/ AFP]](https://www.sochfactcheck.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/WhatsApp-Image-2024-08-28-at-18.09.26.jpg)

Supporters of Khan’s Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) party block the Peshawar-to-Islamabad highway as they protest thePakistan’s national election results, in Peshawar on 12 February 2024 [Abdul Majeed/ AFP]

Considering the violence that took place before and on the day of the election, it is highly misleading to say that the elections took place in a largely peaceful environment, and any definition of largely peaceful that simply dismisses these incidents cannot be considered credible.

- Former Member of the National Assembly, Mohsin Dawar tweeted at 10 am on voting day, announcing that the Taliban have attacked three of their polling agents in Tappi, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

-

Role of party agents (polling agents)

Claims: “While party candidates’ agents were present in most polling stations observed, there were isolated cases of agents not being accommodated in some polling stations during the voting process and, in addition, they could not properly observe the count.”

Rating: False.

Fact: During the crucial process of vote consolidation, after polling had ended, numerous candidates and their agents encountered severe obstructions and discriminatory treatment. According to candidates who shared evidence on social media, and reports from election observers, party representatives were either violently expelled from polling stations and RO offices, or refused access to polling stations altogether. These violations of the Election Act, and the lack of transparency, were systemic and deliberate, not isolated.

According to Section 90 of the Elections Act, 2017, the vote count of each polling station (managed by a Presiding Officer) is documented in a form known as Form 45. After this, Form 45s from each polling station in each constituency are collected by the Returning Officer (RO) of the constituency and consolidated into a Form 47 that documents the results of the constituency. The vote counting in each polling station and vote consolidation by the ROs must take place in the presence of either candidates or their designated representative in order for the exercise to be legally valid. Section 92 of the Elections Act, 2017 states that the RO must announce the result after the consolidation of results received from all presiding officers in the presence of all contesting candidates and their election agents.

Section 95 clarifies that the RO is supposed to give a signed and dated copy of the provisional results to the contesting candidates and final results must be consolidated in the presence of the candidates and their agents. The RO is also supposed to look at the ballot papers excluded by the Presiding Officer to see if he finds any such ballot paper which should not have been excluded.

However, in violation of the legal framework described above, numerous candidates reported being obstructed from participating in the vote consolidation process. On the night of 8 February, numerous candidates were denied access to RO offices, where the crucial task of consolidating results was taking place. Many of these instances were widely reported in the media in the days prior to the publication of COG’s statement.

In NA 128 (Lahore), 25 armed men stormed the RO’s office in Model Town, Lahore, illegally evicting the PTI-backed candidate Salman Akram Raja from the premises. They also physically assaulted a member of his legal team, and refused to let Raja or his polling agent enter the premises until his competitor Aun Chaudhry of the Istehkam-e-Pakistan Party was declared the winner by the ECP.

Raja challenged these actions via a petition before the Lahore High Court on the morning of 9 February 2024, seeking a stay order on the election results of his constituency, which was granted. This story made headline news but was not reported by COG.Similarly, PTI-backed independent candidate, Meher Bano Qureshi of NA 151 (Multan), who is also the daughter of the currently-jailed PTI leader and former minister of foreign affairs, Shah Mahmood Qureshi, said that although all other candidates from her constituency were inside the ROs office, she was stopped at the gate by armed guards who told her that they were working under strict orders to deny entry to her.

A message for the Election Commissioner of Pakistan, Sikander Sultan Raja.@ECP_Pakistan@PTIofficial#NA151 #Election2024 pic.twitter.com/UU5nq3dwy6

— Meher Bano Qureshi (@MeherBanoQ) February 8, 2024

[X post embedded here. Use vpn to view in Pakistan]

In addition to these prominent examples, candidates, journalists, and registered polling agents were denied entry to RO offices at the time of the counting of votes in a number of other constituencies as well. A non-exhaustive list of these constituencies include NA 31 and NA 33 , NA 241, NA 148, PS 105, and NA 48.

As a result, in the days immediately after the election, the courts were flooded with challenges to the vote counts that illegally took place in the absence of candidates and their agents.

It is astonishing that COG’s interim statement characterised such widespread violations of the Election Act as “isolated” and failed to make note of complaints and legal challenges to the vote counting procedures in a number of high profile constituencies.

-

‘Close and Count’

Claim: “The count at polling stations we observed was generally managed efficiently by polling staff”.

Rating: Misleading

Fact: While we cannot comment on the polling stations observed directly by COG mission, as they have not specified which polling stations they observed, contemporaneous reports from a large number of constituencies documented blatant electoral fraud, including ballot box tampering, illegal expulsion of party agents, and counts taking place without party agents – actions in clear violation of the Election Act and Rules. None of this can be categorised as efficient management. In addition, the legally mandated timelines for counting and closing were not followed.

To assess the accuracy of the claim regarding the efficiency of vote counting and closing at polling stations, it is essential to keep in mind the documented procedures and timelines.

The table below provides a step-by-step account of the counting, consolidation, and result announcement process established by the Election Act (and Rules), and highlights significant deviations from timelines mandated by the Act.

Procedure Official Timeline Relevant Sections Timeline followed by ECP Comments Counting Votes Immediately after the close of poll Section 90 of the Election Act 2017 10 February 2024 Counting of votes started after polling closed, but the appropriate method was not followed as many candidates and their polling agents were not allowed to witness the count.. In many cases, polling did not begin on time, the count was halted and the transmission was inexplicably delayed. Publishing Provisional Results Forthwith upon receipt from Presiding Officers. Section 13(2) and (3) of the Election Act 2017:

(2) The Presiding Officer shall immediately take snapshot of the Result of the Count (Form 45) and, as soon as connectivity is available and it is practicable, electronically send it to the Commission and the Returning Officer before sending the original documents under section 90.(3) (3) The Returning Officer shall compile the complete provisional results (Form 47) as early as possible and shall communicate these results electronically to the Commission:

Provided that if, for any reason, the results are incomplete by 02:00 a.m. on the day immediately following the polling day, the Returning Officer shall communicate to the Commission provisional results as consolidated till that time along with reasons for the delay, in writing, while listing the polling stations from which results are awaited and thereafter shall send the complete provisional results as soon as compiled but not later than 10:00 a.m.

Section 13(3) and Section 92 of the Election Act 2017; Rule 84(4) of Rules 2017 22 February 2024 The Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP) began receiving and announcing provisional results, but significant delays were reported. Provisional results were not fully available even until 22 February, well past the legal deadline, causing widespread concerns.

While the first result was announced around 3 am, most constituency results were withheld despite TV channels showing that the count was almost complete.Notice of Consolidation to Candidates Immediately after announcement of provisional results Section 95(1) of the Election Act 2017 9 – 12 February 2024 Notices were issued late due to the delays in announcing provisional results. Recounting Votes (if applicable) Before consolidation proceedings Section 95(5) of the Election Act 2017 11 – 26 February 2024 Recounts were requested in several constituencies, particularly where the margin of victory was narrow. These recounts further delayed the consolidation process. Completion of Consolidation Proceedings 7 days after polling for National Assembly; 5 days for Provincial Assembly Section 95(7) of the Election Act 2017 February – March 2024 Since provisional results were being announced until 16 February, the consolidation process was delayed, and in some cases was not completed until March, according to news reports. Sending Consolidated Results to the Commission Section 95(8) of the Election Act 2017

(8) The Returning Officer shall, within twenty four hours after the consolidation proceedings, send to the Commission signed copies of the Consolidated Statement of the Results of the Count (Form 48) and Final Consolidated Result (Form 49) together with Results of the Count and the Ballot Paper Account, as received from the Presiding Officers, and shall retain copies of these documents for record.Section 95(8) of the Election Act 2017 4 July 2024 Consolidated results were sent to the ECP behind schedule, mainly due to the aforementioned issues with recounting and discrepancies between Form 45s issued to the candidates and Form 47s published by the ECP. Some Form 48s and Form 49s were uploaded by 4 July 2024. Publishing Results on Commission’s Website Within 14 days from the date of the poll Section 95(10) of the Election Act 2017 5 July 2024 The results of Form 45s were not published on the ECP website by the legal deadline of 22 February. In fact, as mentioned earlier, provisional results (Form 47s) of the National Assembly, and some results of Provincial Assemblies were released as late as 16 and 22 February 2024. These significant delays have raised questions over the transparency and legitimacy of the election results. The final Form 45s were uploaded as late as 5 March. Even till late July, some of the PDFs were modified, which shows that the ECP is still tampering with the uploaded forms.

Publishing Final Results in Official Gazette Within 14 days from the date of the poll Section 98 of the Election Act 2017 22 March 2024 The timeline for publishing results in the Gazette was not followed. Even when the results were published, this was done in ignorance of the fact that the results of many constituencies were challenged before the court. Despite ongoing challenges, the ECP announced winners and allowed them to sit in Parliament, rendering the court cases largely ineffective. As documented above, the count, consolidation, and announcement process deviated significantly from what was mandated by the Act. Counting of votes began without the proper procedures, provisional results were announced late, and recounts and result consolidations caused further delays. These lapses in adhering to the statutory deadlines highlight issues with procedural compliance and transparency in the election process.

Furthermore, as noted elsewhere, unofficial results based on Form 45s, broadcast on TV on the night of the election, showed PTI (or affiliated) candidates in the lead in over 150 constituencies. Later that night, candidates were expelled from polling stations, the issuance of Form 45s ceased, and live election coverage was stalled or suspended. Days later, the Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP) released the official results and uploaded Form 47s on their website, despite many candidates not receiving their Form 45s. Notably, the Form 45s were uploaded significantly later than the Form 47s, despite the latter simply being aggregates of the former. This sequence of events alone raises significant concerns about the election’s legitimacy and fairness.

In fact, counts recorded in Form 47s, after candidates were expelled from RO offices, were disputed as early as 9 February 2024. The following is a non-exhaustive list of the same:

- Rabistan Khan, a PTI-backed independent contesting for PS 116 Karachi West 1, told Soch Fact Check that Form 45 reported him receiving 4,067 votes, whereas Form 47 shows only 2,166 votes for him. Conversely, the opposing candidate, Ali Ahmed, is reported to have received significantly more votes on Form 47 (7,085) compared to Form 45 (3,388)

- On 10 February 2024, PTI-backed Khurrum Sher Zaman from NA 241, shared a video of him sitting with the collected Form 45s and going over the vote count, thanking his voters for coming out in his favour and promising to protect the mandate that they have given him. He claimed that on voting day, he received 72,780 votes from NA 241 according to the Form 45s in his possession, and the ECP proclaimed PPP’s Mirza Ikhtiar Baig as the winner with approximately 19,000 votes. However, according to the ECP’s Form 47, Zaman’s votes have been slashed to 48,610.

کب تک۔۔۔۔

#مینڈیٹ_پر_ڈاکا_نامنظور

Posted by Khurrum Sher Zaman on Saturday, February 10, 2024

- According to the constitutional writ petition filed in court by PTI-backed independent candidate for NA 244, Aftab Jehangir, he received 19,497 votes based on Form 45s, while Farooq Sattar from MQM received 7,905 votes. However, in Form 47 this lead was reversed, with Jehangir receiving 14,073 votes and Sattar receiving 20,048 votes.

- Shakeel Ahmed, PTI-backed candidate from PS 121 Karachi West 6, claimed to have Form 45s showing more than 27,000 votes, while MQM received less than 10,000.

- Soch Fact Check confirmed that by 24 February 2024, nearly 80 candidates had approached the courts alleging election fraud and irregularities. Additionally, numerous cases were lodged in the courts and with the Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP), based on recounting requests and other grounds, but were rejected by the ECP citing jurisdictional conflict and election tribunals were set up.

-

Results Management

Claim: “As during previous general elections, we noted the continued efforts at promoting transparency, with the display of the signed Form 45 outside each polling station after counting concluded. We note that these forms were due to be sent via the mobile phone application, but the shutdown of internet and mobile coverage compelled presiding officers to rely solely on manual transmission of the forms. We received reports that this adversely impacted the processing of results. We will reflect on this further in our final report.”

Rating: False.

Fact: A significant number of Form 45s were never displayed outside the polling stations, and were only directly uploaded to the ECP’s official website on 5 March 2024. Many candidates did not receive all the Form 45s from their constituencies, and were instead expelled from RO offices, sometimes violently, and counts were completed in their absence in contravention of election laws. In addition, as noted elsewhere, the Form 45 results that were received by candidates on the night after the election, were contradicted by the Form 47 results published a few days after the election. Finally, when Form 45s were finally uploaded on the ECP’s website on 5 March 2024, several weeks after the assembly was constituted, and in violation of the sequence and timeline for the release of forms mandated by law, they did not tally with those provided to the candidates in the immediate aftermath of the election.

This is evidenced by the glaring irregularities in the Form 45s uploaded by the ECP compared to those given to candidates on election night. These irregularities include overwriting, addition and subtraction of digits on the forms, missing signatures and symbols, and numbers added in one column but not in the final tally of votes counted or polled. Some of these errors are highlighted below in the form of a comparison between the forms uploaded by the ECP and those provided to candidates and later consolidated on various online repositories, including Insafpk.GitHub.io.

In fact, the ECP notably continued to modify the Form 45s available on its official Google Drive, as late as 5 July, according to the modification date visible on the drive. This further raises questions on the legitimacy of the ECP’s official results as well as the transparency of the electoral process.A comparison between the official and candidate data sets may be found here. In particular, the post-election tampering of Form 45s in the case of NA 148, NA 241, and NA 151 was unmissable as the candidates immediately made their copies of the document available to the public on social media on 9 and 10 February 2024 respectively.

Furthermore, an analysis published by Pattan, a civil society organisation, noticed anomalous and improbable turnout patterns in a significant number of official Form 45s for NA 130 and NA 128. Similar turnout patterns, notably absent from candidates’ Form 45s, have been detected in official Form 45s from across the country.

Discrepancies between candidates’ Form 45s and the consolidated Form 47s issued by the ECP were noted widely, and not just in isolated instances.The cumulative impact of Form 45 anomalies, similar to the above, is an entirely different electoral map and election outcome. The stark contrast between the results derived from the two different sets of Form 45s is visualised below.

Why did we fact-check this statement?

Election observers have a responsibility to safeguard election integrity and uphold the democratic process. The Commonwealth Observers Group in particular play a crucial role in shaping local discourse, as well as global perceptions, regarding the transparency and legitimacy of elections held in Commonwealth member states. As such, the Commonwealth Observers Group (COG) is responsible for providing an objective, accurate and comprehensive assessment of the elections they monitor. Unfortunately, in the case of Pakistan’s elections, COG’s inaccurate claims and omission of crucial facts has bolstered misleading and false narratives about the transparency and integrity of the electoral process.

The words of election observers matter greatly. For instance, when on the eve of the General Election 2024, the Head of COG Dr Goodluck Jonathan falsely claimed that the suspension of internet services would not affect the election, it was reported on widely in the media. By normalising internet disruptions, the statement provided space for the authorities to justify turning off mobile internet. In addition to making election services unavailable, such as the 8300 helpline, the lack of cellular connectivity also directly caused problems with the functionality of the EMS, which in turn enabled irregularities in counting and consolidation.

Subsequently, in the aftermath of the election, COG’s interim statement was referenced by various media outlets and social media users as an endorsement of the election. For example, one Instagram page claimed that COG is “satisfied with [the] polling process,” while Dunya News stated that “the Commonwealth Observers Group commended Pakistan’s commitment to holding peaceful and successful elections.” Similarly, The News International reported, “COG delegation visited the polling stations of NA 47 Islamabad and expressed satisfaction over the polling process besides declaring it fair and transparent.”

In an environment where the ECP’s official results are currently being disputed before election tribunals, COG’s interim statement discredits the cases of the many candidates who have challenged election results, and is dismissive of the thousands of credible first-hand reports of rigging and electoral misconduct on social media. Notably, the statement minimises the volatile security situation which prevailed across the country in the days leading up to the polls.

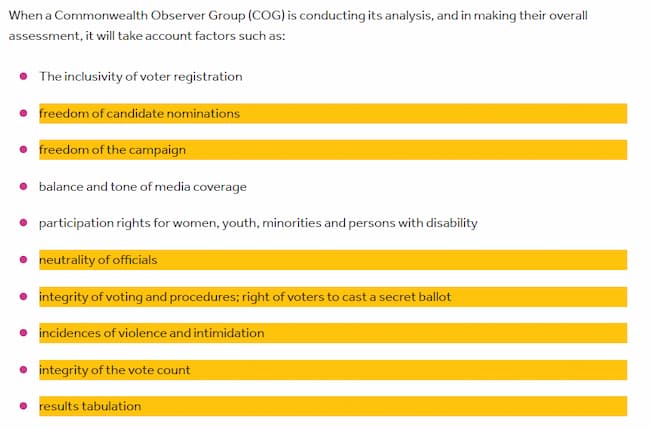

Besides the crucial omissions and objectively misleading claims, COG’s interim statement also fails to uphold the group’s own updated observation guidelines for elections in the Commonwealth nations. According to the guidelines, COG missions must comprehensively evaluate 10 essential elements of the elections they observe. However, the interim statement failed to accurately or fairly assess at least seven of those elements.

Revised Commonwealth Guidelines for the Conduct of Election Observation in Member Countries

Moreover, as documented above, COG’s statement overlooks a wide range of human rights violations against candidates in the months leading up to the 2024 election. It fails to mention severe restrictions on mainstream media, including a well-documented ban on using Imran Khan’s name in print and on television. Omissions of such violations, ignore COG’s own guidelines for election observation, including freedom of candidate nominations, neutrality of officials, and freedom of the campaign.

Thus, in the course of failing to meet evidence based reporting standards and presenting an inaccurate picture of the elections, the interim statement failed to adhere to several of its own prescribed guidelines as well.

Finally, when it comes to assessing the neutrality of officials, COG’s report fails to mention the role of the military in shaping the pre-poll environment or their influence over the election itself. In addition to the reasons stated above, the military’s historical and enduring influence over the Pakistani political system, which has been covered by every major publication including The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, Le Monde, Der Spiegel, The Times, and the BBC, was left out by COG. This raises serious questions about the credibility and neutrality of their interim statement, and more generally, their election observation process.

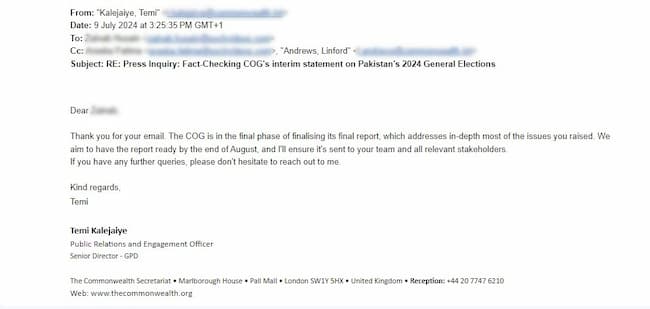

The unexplained and unprecedented delay in publishing a final report in the case of these elections further calls into question the political independence of COG mission. Typically, in the past, the group uploaded its final reports within four to five days after the election, as shown in Table 1. In a press release on 10 February 2024, COG committed to publishing its “full findings on the entire electoral process” in the form of a publicly available final report.

On 9 July 2024, COG’s Public Relations and Engagement Officer informed Soch Fact Check they would publish the final report by the end of August

Following up on this commitment, Soch Fact Check first corresponded with COG in February to inquire about the claims made in their interim statement. We then contacted the group multiple times to request a final report. On 9 July 2024, COG informed Soch Fact Check they would publish the final report by the end of August, without offering any explanation for the unprecedented delay, despite our enquiries. As August is now ending, in the absence of a final report, the Interim Statement stands as the only public observation from the Commonwealth regarding the election: failing to fact-check it would allow consequential misinformation to remain in circulation.

| Election | Election Date | Commonwealth Report Published |

|---|---|---|

| Nigeria Presidential and National Assembly Elections 2023 | 25 February 2023 | 22 April 2023 (1 month and 26 days) |

| Kenya General Elections 2022 | 9 August 2022 | 14 August 2022 (4 days) |

| Bahamas General Election 2021 | 16 September 2021 | 23 September 2021 (5 days) |

| Sri Lanka Presidential Election 2019 | 16 November 2019 | 22 November 2019 (5 days) |

| Zimbabwe Harmonised Election 2018 | 30 July 2018 | 30 July 2018 (0 days) |

| Pakistan General Election 2013 | 11 May 2013 | 16 May 2013 (4 days) |

| Kenya General Elections 2013 | 4 March 2013 | 10 March 2013 (5 days) |

| Zambia General Elections 2011 | 20 September 2011 | 26 September 2011 (5 days) |

| Papua New Guinea National Election 2012 | 23 June – 13 July 2012 | 16 July 2012 (2 days) |

| Sierra Leone National and Local Council Elections 2012 | 17 November 2012 | 23 November 2012 (5 days) |

| Ghana Presidential and Parliamentary Elections 2012 | 7 December 2012 | 14 December 2012 (6 days) |

| Guyana National and Regional Elections 2011 | 28 November 2011 | 4 December 2011 (5 days) |

| Lesotho Parliamentary Elections 2012 | 26 May 2012 | 31 May 2012 (4 days) |

| Nigeria National Assembly and Presidential Elections 2011 | 9 and 16 April 2011 | 21 April 2011 (4 days) |

| Uganda Presidential and Parliamentary Elections 2011 | 18 February 2011 | 24 February 2011 (5 days) |