Last month, on 15 December 2020, President Arif Alvi approved a set of laws that included court ordered chemical castration as a penalty for sexual violence. Soch Fact Check debunks 3 common myths about chemical castration and its impact on sexual violence.

Claim 1: Chemical castration is a permanent procedure that stops a person from committing rape.

Claim 2: Sexual violence is a result of hormone levels and sexual urges.

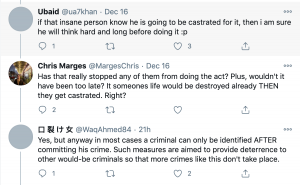

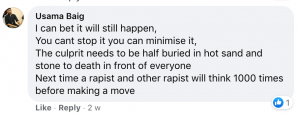

Claim 3: Potential offenders will be less likely to rape if they are afraid of being castrated.

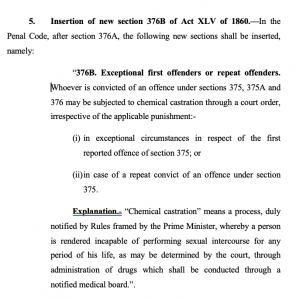

Criminal Law (Amendment) Ordinance 2020

What Exactly is Chemical Castration?

Chemical castration is a form of medical intervention that seeks to influence men’s sexuality by working on the body’s hormonal function. All methods of chemical castration currently in use impact the body’s secretion and/or metabolization of testosterone. Depending on the medication being used, chemical castration may also impact other hormones, such as dihydrotestosterone (DHT). Both testosterone and DHT are classified as androgens, which are a group of hormones that influence the development and functioning of the male reproductive system.

Depending on the method being used, chemical castration also impacts the follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH). The release of FSH and LF is dependent on the gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH), which is also affected during chemical castration. Currently, chemical castration is carried out using two types of drugs: antiandrogens, namely medroxyprogesteron acetage (MPA) and cyproterone acetate (CPA), and GnRH analogues. These medicines all work in different ways in impacting the balance of the aforementioned hormones.

Claim 1: Chemical castration is a permanent procedure, which guarantees that an offender will not commit a sexual crime again.

Fact: Chemical castration is a reversible treatment and cannot physically stop an individual from committing sexual crimes.

Soch Fact Check found that chemical castration is a reversible procedure. According to the Journal of Korean Medical Science, “chemical castration is no longer effective after it is discontinued; therefore, the spontaneity for receiving medication is a prerequisite to overcoming this limitation”. The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry’s (WFBSP) supports this research.

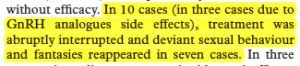

In a meta-analysis studying the impact of both antiandrogens and GnRH analogues, WFBSP concluded that the effects of both CPA and MPA were “completely reversible” 1 to 2 months after medication was interrupted. WFBSP also cites studies that report, “increased recidivism after MPA was stopped,” recidivism meaning reoffense of sexual misconduct.

Moreover, WFBSP reported evidence supporting the reversible nature of GnRH analogues. They also cited two cases who reported a recurrence of what they define as “deviant” sexual fantasies and behaviour within 8 to 10 weeks of treatment being interrupted at 12 and 34 months, respectively.

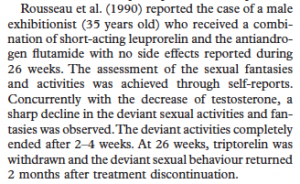

WBSP cites evidence for return of certain behaviours and fantasies after discontinuation of GnRH analogues.

WBSP cites a study that reports a return of certain sexual behaviours after discontinuation of GnRH analogues.

WFSBP reports that the optimal duration of treatment necessary for either antiandrogens or GnRH analogues remains unclear so far. Furthermore, they also report that “failure to complete treatment was associated with higher risk of recidivism of sex offences” and that, “hormonal treatment must not be abruptly stopped”. A study of 38 Korean patients also reported, “an unexpected upsurge of testosterone levels with intense sexual drive and fantasy … during the first 2 months after cessation of treatment”.

Speaking about the Criminal Law (Amendment) Ordinance 2020, Saroop Ijaz, Senior Counsel of the Asian Division of Human Rights Watch points out that need for continuous, uninterrupted treatment in chemical castration, “assumes an elaborate structure of monitoring the whereabouts of convicts,” once they have been released into society and also necessitates the creation of a, “medical infrastructure to monitor [regular] doses,” of the medication.

The state, “can’t do a polio immunisation drive, now you are asking for violent criminal offenders to be administered this medicine by health workers,” states Ijaz. “You think you have the capacity and the willingness, you have the intuitiveness. If the criminal justice system does not even have the wherewithal to investigate cases and convict people, it does not matter what happens to the very few people who are convicted.”

Sahar Bandial, an Advocate of the High Courts echoes Ijaz.There would be no need for chemical castration if an offender is not being released into society, she points out. If they are, the system would require them to regularly report for treatment, with penalties in place if they don’t. This requires a mechanism that ensures a degree of regularity with checks and balances. This seems unrealistic, considering the many problems in the systems that are already in place, such as,“a lack of coordination, loopholes in investigation, police reporting, evidence collection,” she says.

Evidence that supports the use of chemical castration as a deterrent for reoffense should be approached with caution, according to WFSBP. Inconsistencies across studies – in factors such as the criteria used to measure effectiveness of treatment and follow-up periods – and methodological flaws make it difficult to draw conclusive results. “In general, the quality of the evidence base supporting the use of all these treatments is rather poor,” the WFSBP’s states, and, “little is known about which treatments are most effective, for which offenders, over what duration, or in what combination”.

Claim 2: Sexual violence is a product of hormone levels and an expression of sexual urges.

Fact: Sexual violence results from a confluence of social, psychological and physiological factors.

Chemical castration is being lauded as an all-rounded cure to sexual urges, particularly those urges that lead to violence against children and gender minorities. This is, in part, related to the belief that hormones govern the level and nature of one’s sexuality.

Soch Fact Check found that there is no conclusive evidence linking hormone levels with sexual urges and fantasies. A study published in the Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law states that, “Our results do not support the idea that abnormal hormone levels explain sexual offending.” The same study suggests that testosterone is not, “related to risk of sexual reoffense”. While it found that LH levels correlate with sexual and violent reoffense, it also stated that because, “the relationship was relatively small, and this is the first study we are aware of,” that shows such results, further research is required to draw conclusive results.

Citing two other reports, the aforementioned study states that, “chemical castration appears to be ineffective in antisocial or psychopathic sex offenders who do not suffer from paraphilia … and certain comorbidities may preclude effective intervention”.

WFSBP supports this, “In all cases, treatment of comorbidities is necessary.” It further states, “hormonal treatment should be part of a comprehensive treatment including psychotherapy and, in most cases, behavioural therapy”.

“Sex offenders employ distored patterns of thinking,” explains the WFSBP, “which allow them to rationalize their behaviour, including beliefs such as children can consent to sex with an adult and/or victims are responsible for being sexually assaulted”.

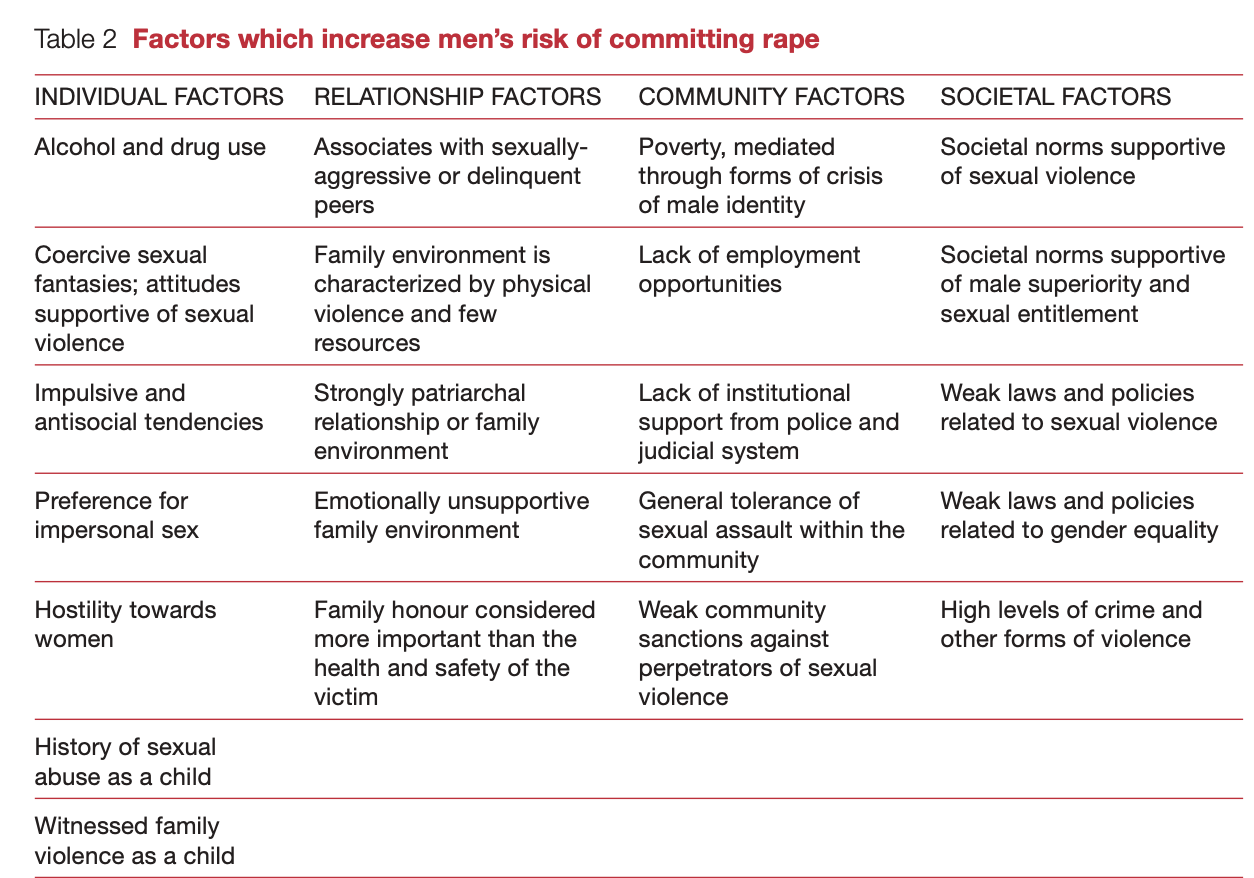

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention lists several factors that contribute to sexual violence and are unrelated to sexuality and hormones. These include relationship factors like a family environment characterized by physical violence, community factors such as general tolerance of sexual violence within one’s community, and societal factors like norms that maintain male superiority over other genders.

The World Health Organization also confirms this.

Source: World Health Organization

“Work with sexual offenders has confirmed that the motivating factor for sexual violence is not sexual desire,” according to the WHO. It goes on to say that the, “underlying factors in many sexually violent acts are power and not, as is widely perceived, a craving for sex. It is a violent, aggressive and hostile act used as a means to degrade, dominate, humiliate, terrorize and control women. Sex is merely the medium to express various types of non-sexual feelings such as anger and hostily … as well as a need to control, dominate and assert power.”

Dr Asha Bedar provides evidence from her work with perpetrators and victims of sexual violence in Pakistan. She recalls her experience of working with a survivor of abuse who was repeatedly abused with objects by a person who was impotent. Men who are unable to perform will sometimes get pleasure merely from watching sexual violence.

In her work, she’s found that reasons for committing rape very rarely have to do with sex alone, or even sex at all. “There’s no sexual disorder because of which you rape or murder. Testosterone can produce a sexual urge but it can’t produce a criminal act.”

Rapists may have felt a lack of control in their lives and, in their need to feel a sense of power, they turn to sexual violence against those they perceive as weaker than themselves. To them, this as an affirmation of their masculinity and power. Dr Bedar has seen cases where rape has been used as a tool for revenge, for example in getting back at someone for romantic rejection.

“When you’re trying to humiliate somebody, particularly a woman, rape is one of the most powerful tools,” says Dr Bedar. “A woman loses her sense of control immediately, nothing will take away her sense of dignity the way rape will. It is an immediate and distinct display of power.” Power dynamics, she further adds, are almost always at play in sexual violence.

The power that offenders derive from sexual violence is an extension of society’s outlook towards women and transgender people, says Dr. Bedar, echoing WHO and CDC’s research. It’s rooted in the way that men are brought up to think about themselves, about power dynamics in society, and about gender minorities. If you see gender minorities being objectified within your families, by society’s institutions, by the media, you can be led into believing that they can be objectified for sex, she says. Sexual violence is a confluence of toxic masculinity, misogyny, and anger towards women.

“Chemical castration is based on this erroneous belief that sexual violence is about sexual urges,” says Dr Bedar, “this is a dangerous belief because it is not addressing the root causes”.

Claim 3: Severe punishments like chemical castration will deter potential offenders from committing sexual violence.

Fact: Severity of punishment is not a social deterrent to sexually violent crimes.

Soch Fact Check could not find empirical evidence supporting a correlation in changes between occurence of sexually violent crimes and implementation of chemical castration in countries where the punishment has been adapted.

According to a report published in The University of Chicago Press’ journal Crime and Justice, it is the certainty of punishment or, more precisely, the certainty of being caught and apprehended, that is a more likely deterrent for crime than severity of punishment.

Sara Malkani, Advocacy Advisor for the Center of Reproductive Rights in Asia, cites the 3% conviction rate for rape cases as evidence that the introduction of chemical castration itself will not serve as a deterrent to sexual violence. Potential offenders aren’t going to be deterred by any manner of extreme punishments if the chances of being convicted is so low, she says.

Dr Bedar echoes this, “Everybody here knows that the possibility of being convicted is very low,” she says. Any form of punishment will not deter a potential offender, she adds, “if it won’t lead to punishment”.

Saroop Ijaz calls chemical castration a “public spectacle,” that panders to society’s appetite of violence. He cites the case of England in the 1800s, where thieves, including pickpockets, were publicly hanged. The irony, he says, was that the public would often gather to watch thieves who had picked pockets at previous hangings being walked to the gallows. These thieves had neither been scared nor deterred by the spectacle of public hangings, he says.

“We’ve been here for honour killings and child marriage,” says Ijaz. Implementing stricter punishments did not lead to a decrease in crimes in these cases.

The severity of punishment for rape itself was at a pinnacle during Zia ul Haq’s regime, when a man was publicly hanged for raping a minor in 1983. Despite this, eleven cases of rape against minors were reported within the next nine years, at least four of these in the city where the man was hung. Neither the hanging, nor the fact that the body was left to hang in full view of the public for a whole day afterwards, proved to be an effective deterrent against the crime.

Both Ijaz and Dr Bedar agree that the possibility of being chemically castrated, in fact, “encourages violence in the offender,” as Dr Bedar says. Offenders are more likely to murder victims to avoid being identified when stricter punishments are mandated.

“Laws are only as good as the people investigating, prosecuting, and adjudicating — the people implementing them ” says Ijaz, “By implementing violent punishments, you seek to exempt yourself of real reform at the level of the police, the lawyers and the judges.”

Summary:

- Chemical castration is a reversible treatment and cannot physically stop an individual from committing sexual crimes.

- Sexual violence results from a confluence of social, psychological and physiological factors.

- Severity of punishment is not a social deterrent to sexually violent crimes.