Claim: The Supreme Court directed the Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP) to print identifiable and traceable ballot papers using technologies like barcodes and serial numbers.

Fact: The Supreme Court made provisions for (ECP) to use technology during all elections and recognized that practical considerations may temper ballot secrecy. It did not obligate ECP to take any specific action for the Senate Elections.

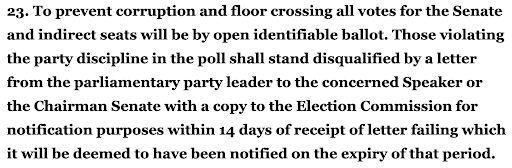

Senate elections: Mechanism

Senate elections: The buildup

Open ballot: The legality

Supreme Court of Pakistan: Advisory opinion

Advisory opinion: Misleading interpretations

Senate elections: The conclusion

Summary

Senate elections: Mechanism

Elections for 52 seats in the upper house of parliament, the Senate, were held on 3 March. During polling, members of the four provincial assemblies and the National Assembly elect representatives from amongst themselves to fill allotted seats in the Senate. Polling is carried out via a secret ballot, whereby each voter’s decision is made in secrecy, with the guarantee that their ballot paper will not be seen by anyone else.

Representatives of the Punjab Assembly had already been elected unopposed in February, while representatives from Sindh, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP), Balochistan, Sindh, and Islamabad were elected last week.

Senate elections have been the subject of much controversy in the past. Party leaders are often heard accusing each other of horse-trading i.e. buying votes for their own candidates from members of other parties. After the 2018 Senate elections, Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) announced that it was taking action against 20 of its own members for selling their votes to other parties. Earlier this year, KP’s law minister resigned after footage emerged of certain provincial assembly members counting cash that was purportedly received in exchange for voting across party lines during the 2018 elections.

Senate elections: The build-up

[extlsc id=”2254″]

Open ballot: The legality

The concept of an open ballot is not new. Despite PML-N and PPP’s opposition to the idea over the past year, open ballot for Senate elections is also mentioned in the Charter of Democracy, signed in 2006 between Benazir Bhutto and Nawaz Sharif.

Charter of Democracy, 2006, signed between Benazir Bhutto and Nawaz Sharif

While briefing the cabinet in December, AGP Khan outlined two legal opinions on the possibility of conducting Senate elections with an open ballot. He stated that amending Article 122(6) of The Elections Act could provide for an open ballot. Article 226 of the Constitution would also have to be amended, he explained, since it states that all elections under the Constitution, other than those of the prime minister and chief ministers, are to be held by open ballot. Since no legislation that stands in contradiction of the Constitution is held as valid, it is necessary to amend Article 226 in tandem with the Elections Act.

AGP Khan also expressed an alternative understanding of Article 226, citing a 2017 case between the Muttahida Qaumi Movement and the Province of Sindh (PLD 2017 Sindh 169). In this case, the Sindh High Court ruled that local government elections fall under Article 226 and thus must be held via secret ballot. This judgement was appealed in the Supreme Court, however, which ruled that local government elections do not fall under the Constitution and, thus, can be held via show of hands as well.

AGP Khan stated that this ruling creates the possibility of interpreting Article 226 as not applying to Senate elections, the mechanisms of which are outlined in the Elections Act 2017, rather than the Constitution. The elections could thus be seen as being held under statutory law and not under the Constitution. AGP Khan recommended that the Supreme Court’s opinion be sought to obtain clarity on the matter by filing a reference, which he later did on behalf of President Arif Alvi in December.

Muhammad Haider Imtiaz, Advocate of the High Court, explains the difference between the Constitution and statutory law: the legislation operates at multiple levels i.e. the Constitution, statutory legislation (acts, ordinances made by statutory bodies such as the parliament) and sub-legislation (by-laws, etc.). The Constitution is the supreme law, on the basis of which parliament legislates, and provincial laws and acts are made. No legislation can be made in contradiction to the Constitution, all statutory laws must be created within its boundaries, he explains.

In the specific context of the Senate polling, the question that the reference asked is whether these elections are held under the Constitution or under The Elections Act 2017, which is the statutory law in this case. It stated that the application of secret ballot to the Senate elections was not a Constitutional mandate but rather only due to statutory provisions, i.e. Article 122(6).

Supreme Court of Pakistan: Advisory opinion

During the course of the proceedings, the Supreme Court heard the Attorney General of Pakistan, and Advocate Generals of Islamabad and four provinces. Counsels representing ECP (who was not in favour of an open ballot), Sindh High Court Bar Association, Pakistan Bar Council, and various political parties, including Pakistan Peoples Party and Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz, also gave testimonies.

In it’s advisory opinion, the bench states that Senate elections “are held ‘under the Constitution’ and the law”. Meaning that, while details regarding mechanisms of elections are laid out in The Elections Act, they do fall under the provisions of the Constitution.

The advisory opinion goes on to reiterate the mandate and responsibilities of ECP in carrying out elections “honestly, justly, and fairly” while guarding against corrupt practices. The bench also cites Article 222 of the Constitution which allows parliament to legislate on “the conduct of elections” and “matters relating to corrupt practices” but mentions that all such legislation is “subject to the constitution” and cannot have the effect of “taking away or abridging any of the powers of the Commissioner or [the] Election Commission”. Article 220 of the Constitution is also cited, as a reminder that all federal and provincial executive authorities are obligated to assist the Election Commissioner and ECP in discharging their duties.

On the matter of the secret ballot, the Supreme Court bench states that secrecy of the ballot is not “absolute” and quotes a judgement from a previous case: “the secrecy of the ballot, therefore, has not to be implemented in the ideal or absolute sense but to be tempered by practical considerations necessitated by the processes of election”.

The judgement cited in this particular instance, from a case in 1967, makes provisions for very specific situations in which secrecy may have been tempered, such as if a handicapped person willingly waives his right to secrecy by seeking the help of another person to write on the ballot paper, or if secrecy is compromised due to an error committed by a presiding officer at a polling station. The judgement states that such situations need not automatically lead to ballot papers being rejected.

The advisory opinion ends by stating that, in carrying out its mandate of ensuring just and fair elections, ECP “is required to take all available measures including utilizing technologies”.

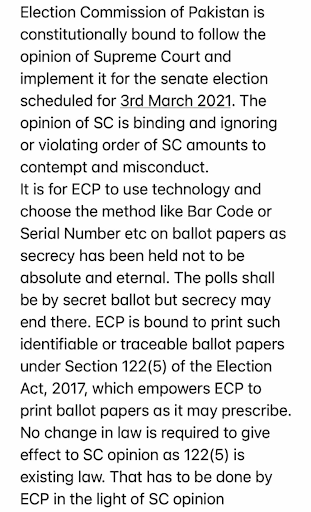

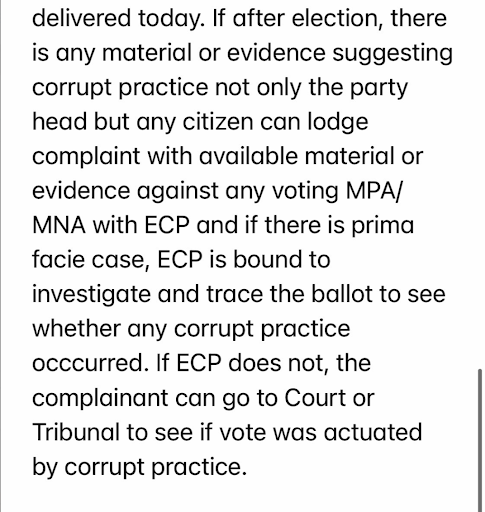

Advisory opinion: Misleading interpretations

While speaking to the media right after the advisory opinion was announced, PTI’s Senator Faisal Javed stressed that the Supreme Court has said that “secrecy is not absolute” and went on to state that this means secrecy could not be held till “the Day of Judgement”. He called the advisory opinion a “victory for Pakistan” because “when there is an identifiable vote, when it is known who has voted for whom, no one will dare sell their vote for money”.

Federation Minister for Information and Broadcasting Shibli Faraz echoed this interpretation in his press conference. According to him, the Supreme Court bench had said that, “secrecy of the ballot is not permanent”. He requested ECP to use technology like bar codes and serial numbers to implement this provision.

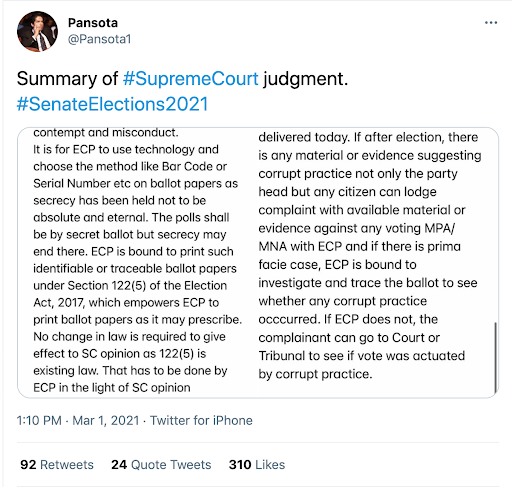

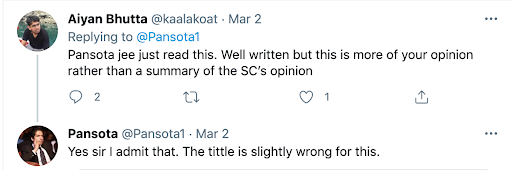

The same day, Barrister Muhammad Ahmad Pansota, who writes op-ed pieces, and has appeared on television and online channels, tweeted an opinion on the Supreme Court’s short order that echoed PTI’s stance. He termed this opinion a “summary”.

Barrister Pansota’s tweet

The next day, he clarified that the text was more of an opinion, but also retweeted it as an “explanation”.

Nevertheless, the tweet was shared as an explanation and summary of the Supreme Court’s advisory opinion by those who had not read the text of the opinion itself.

The text of Pansota’s tweet was also quoted verbatim by Dawn and attributed to AGP Khan. Soch Fact Check reached out to Pansota, who stated that he was the original author of the statement, which he expanded on in an op-ed written for Geo.

Soch Fact Check reached out to Dawn, as well as a representative of AGP Khan, for clarity on why the statement has been attributed to the attorney general in the above mentioned article. Neither was available for comment.

Text of Barrister Pansota’s opinion

We also reached out to four legal experts for their views on the Supreme Court’s advisory opinion and how Pansota and PTI lawmakers’ interpretations of the short order compare to the original text of the advisory opinion itself.

Barrister Zainab Janjua, an advocate of the high courts who was present in court during the case, points out that Pansota’s opinion is based on observations made by the judges’ bench during proceedings. These observations did not, however, make it into the short order. They may or may not be included in the detailed opinion but, for now, the interpretation expressed by Pansota stands as inaccurate she states because, “It is important to distinguish between observations made during proceedings and the short order itself.”

On the matter of secrecy, Barrister Asad Rahim Khan points out that the advisory opinion states that secrecy is not “absolute” but does not use the word “eternal” like Pansota has done. Attaching this word to the advisory opinion, he feels, attaches implications that are not present within the text itself, namely that the ballot might be secret on the day of elections but this secrecy can later be challenged.

Janjua explains that, during the proceedings, the bench brought up questions on the time period till when secrecy applies to the ballot. The judges stated that the ballot’s secrecy could perhaps be interpreted as being applicable only till when it is being cast. The ballot could be opened later, they suggested, in the event that evidence of corrupt practice require it.

These questions and observations did not, however, make it into the advisory opinion, as Janjua points out. Haider Imtiaz states that without even going into the details of the previous judgement from 1967 that has been cited, a very “common sense” reading of the advisory opinion tells us that secrecy of the ballot can be tempered in very specific conditions when the practical considerations of the election process warrants it. The Supreme Court has left it at that,” he points out, “The advisory opinion doesn’t say that you can temper the ballot’s secrecy to curb corrupt practices,” he points out.

Janjua explains that the clause on secrecy can be better understood when read in tandem with the judgement of the case it cites. The judgement, firstly, refers to general elections, which already have legislative mechanisms in place for investigating corrupt practices. In the case of a handicapped person, as the judgement mentions, secrecy is tempered voluntarily, which is a very specific context.

Ahmed Bilal Mehboob, president of the Pakistan Institute of Legislative Development and Transparency echoes this opinion. The judgement that the Supreme Court cites in its clause on secrecy reflects that secrecy is not absolute in very specific contexts. The guiding principle of the extent to which secrecy is not absolute, and the context in which to apply this principle for Senate elections has been left up to ECP, he feels.

Both Janjua and Imtiaz agree that the Supreme Court might expound on what it means by “practical considerations” in a detailed opinion later on. Imtiaz, however, feels that this would be beyond the scope of the questions that the presidential reference asked. As it stands, the advisory opinion did not obligate the ECP to act in any specific manner during the Senate elections, including printing identifiable ballots that could be traced to each voter with serial numbers or barcodes.

The option of barcodes and serial numbers, says Janjua, was suggested during the proceedings by Justice Ijaz ul Ahsan, who suggested that this information could be accessible exclusively by ECP. The Election Commissioner objected to this stating that this would be no different than having a voter’s name on the ballot number. Again, Janjua stresses that Justice Ahsan’s suggestion did not make it into the advisory opinion itself. “They would have simply stated in the short order that ballot papers should be identifiable,” she states.

Mehboob reiterates Janjua’s point, and states that AGP Khan also brought up the possibility of barcodes behind ballot papers. People saw that there was a mention of technology in the advisory opinion, combined it with observations and suggestions made during proceedings, and inferred that ECP had been directed to attach barcodes and serial numbers to ballot papers, he states.

Mehboob himself is opposed to the idea of identifiable ballot papers and is of the opinion that Article 226 of the Constitution will have to be amended to make provisions for them. Even if the barcodes or serial numbers are only accessible to ECP, the idea will make voters very uncomfortable, he states. They will not exercise their vote with the same confidence and comfort. “Either there is secrecy or not secrecy. There is no partial secrecy. In our country, there can be security implications of a person on the basis of their vote,” he states, In the Sindh Assembly, right inside the assembly there was a beating.”

So why does the advisory opinion specify the use of technology in carrying out ECP’s mandate?

“This is where the Supreme Court has tried to refrain from specifying exactly what ECP ought to do,” explains Janjua. During proceedings, the bench asked ECP what measures they undertake to ensure that elections are fair. ECP explained that during general elections they use mechanisms like counterfoils and biometric verification from NADRA’s database, all of which there is precedence for in the law.

Mehboob explains that, when investigating corrupt practices, ECP may compare thumbprints of a voter on a counterfoil and the electoral roll to ensure that the prints match. This is, however, a relationship between the counterfoil and the electoral roll, he points out. There is no relationship between the ballot paper and the counterfoil, the ballot paper is not opened at any point or checked against the counterfoil.

Both Mehboob and Imtiaz point out that the Supreme Court has stopped short of specifying what technologies ECP can and should use in carrying out its mandate and responsibilities. Janjua states that while the ECP is generally obligated to enforce just and fair elections, and bound to investigate if there is evidence of corrupt practice, to say that the Supreme Court is saying that they are required to investigate and trace ballots is not accurate at all.

Text of Barrister Pansato’s opinion

Imtiaz explains that election law provides remedies against grievances at every stage of the election process from delimitation of constituencies, to nomination of candidates, to the polling process. He also agrees that ECP is bound to investigate corrupt practices but to say that this advisory opinion is directing the commission to trace and investigate ballot papers is conjecture at this point.

By mentioning the use of technology and stating that secrecy is not absolute, states Imtiaz, the Supreme Court has opened a door for ECP, making provisions for the commission to temper secrecy in investigating corrupt practices should it choose to. It has also allowed for future legislation that makes provisions for traceable and identifiable ballot papers. But the advisory opinion stops here.

To say that it has bound the commission to do anything is “wishful thinking,” Imtiaz states. If Pansota’s opinion was accurate, ECP would have postponed the Senate elections and applied the directives that it stipulates the Supreme Court as having made, Imtiaz points out. However, since the advisory opinion, as it stands in the short order, has left it up to ECP to apply its provisions, the commission acknowledged the suggestions made and chose to carry out Senate elections as per past protocol.

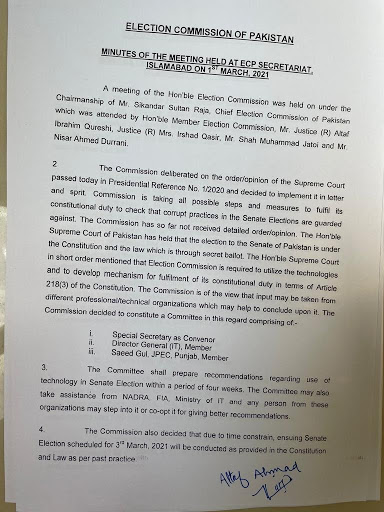

Senate elections: The conclusion

On 2 March, ECP released a press release stating that it had taken the Supreme Court’s advisory opinion into account and had formed a committee to explore how it can implement its recommendations. The press release also stated that, due to time constraints, the commission had decided to carry out this year’s Senate elections as per past protocol.

ECP’s press release

While PTI emerged as the majority party in the Senate, the opposing alliance still managed to emerge with more seats in the Senate, with 53 seats against the ruling alliance’s 47 seats. PTI also suffered a major setback in the Islamabad Capital Territory, where the opposition alliance’s candidate Yousaf Raza Gillani was voted as a representative into the general seat by the National Assembly, beating PTI’s Hafeez Sheikh. PTI National Assembly members would have had to vote for Gillani for him to win this seat.

After results were announced, Prime Minister Imran Khan addressed the nation. He stated that when he first came into politics, he realized that the Senate elections are, “run on money,” and decided to campaign for open ballots.

Addressing ECP, PM Khan questions why the commission insisted on a secret ballot and accuses it of falling short of its mandate. “Does the constitution allow the bribery that has been going on for thirty years,” he asked. “Even though the Supreme Court allowed you to … keep identification of the ballot so that we could find out who the people are who have sold themselves today,” he states, “You protected those criminals and you caused harm to our democracy.?”

PM Khan went on to state that all of PDM’s parties ganged up and insisted that there should be a secret ballot. He asked the nation to question why these parties, who had previously spoken of an open ballot in the Charter of Democracy, were calling it undemocratic and unconstitutional when PTI had campaigned for it.

Summary: On 1 March, the Supreme Court released its advisory opinion on the Senate elections. Many interpreted it as directing ECP to print identifiable and traceable ballot papers that could later be used to investigate corrupt practice. Speaking to legal experts, Soch Fact Check found that the short advisory opinion did not direct the ECP to take any such steps.